From songlines to science: Bridging healthcare and Indigenous culture

Interview with Prof Gareth Baynam, medical director, Rare Care Centre, Western Australia

Estimated reading time: 9 minutes

Gareth Baynam has pioneered an innovative project translating medical terminology into Aboriginal languages. By pairing Indigenous youth with their elders, the project bridges cultural heritage with modern medicine, aiming to address the inequities in healthcare many Indigenous people face

In 2016, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution proclaiming 2019 as the international year of Indigenous languages (IYIL). The United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous issues said that, at that time, 40% of the estimated 6,700 languages spoken around the world were in danger of disappearing, most of which are indigenous.1 The aim of the IYIL, was to promote and protect Indigenous languages and lessen the isolation many Indigenous people encounter.

“Indigenous languages add to the rich tapestry of global cultural diversity. Without them, the world would be a poorer place.”2

In 2019, in response to the IYIL, Gareth Baynam, medical director of the Rare Care Centre in Western Australia, contacted UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) with a proposition to explore language translations for Indigenous people. The basic concept was to pair Indigenous youth with family members and elders to translate their native languages. “Through this initiative you connect across generations and get intergenerational knowledge transfer. The elders love it because they’re passing on all the wisdom and cultural learnings and the youth love it because they’re better connected to their culture. It’s a social benefit for all.”

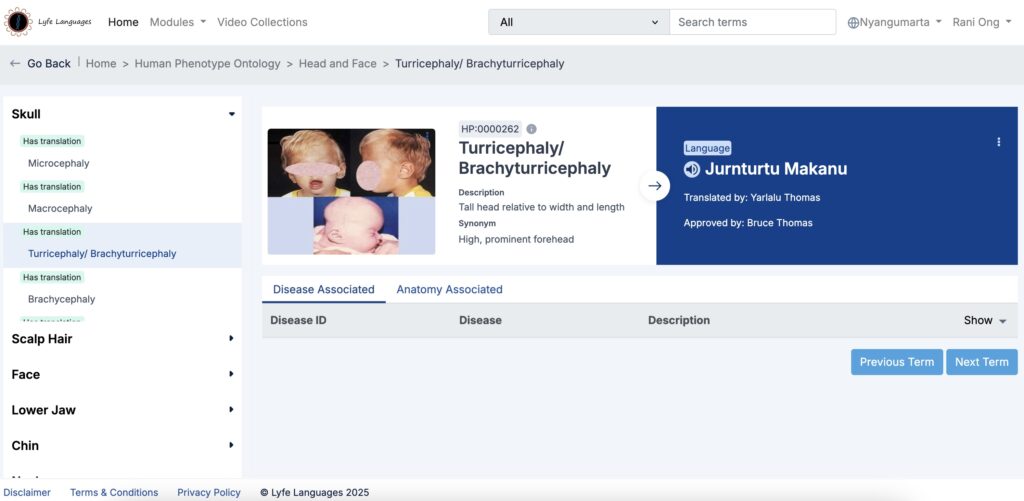

Gareth wanted to create a scalable way to repurpose the language translations for different applications, one being medical outputs. Utilising the Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) was, for Gareth, the perfect place to start. The HPO is a database that provides a standardised vocabulary of phenotypic abnormalities found in human disease that is widely used in precision medicine diagnostics and for natural history studies. “Fortunately, we’d done some work years earlier, translating the scientific speak into lay language, and so we approached communities with this lay language for them to translate. That was really the genesis of it.” Using the ontology is the bridge to genomic diagnostics, registries, natural history studies, treatment monitoring and drug repurposing. “It is a fantastic way to blend the oldest cultures on our planet with the newest technologies through a shared language.”

A RARE and innovative place to start

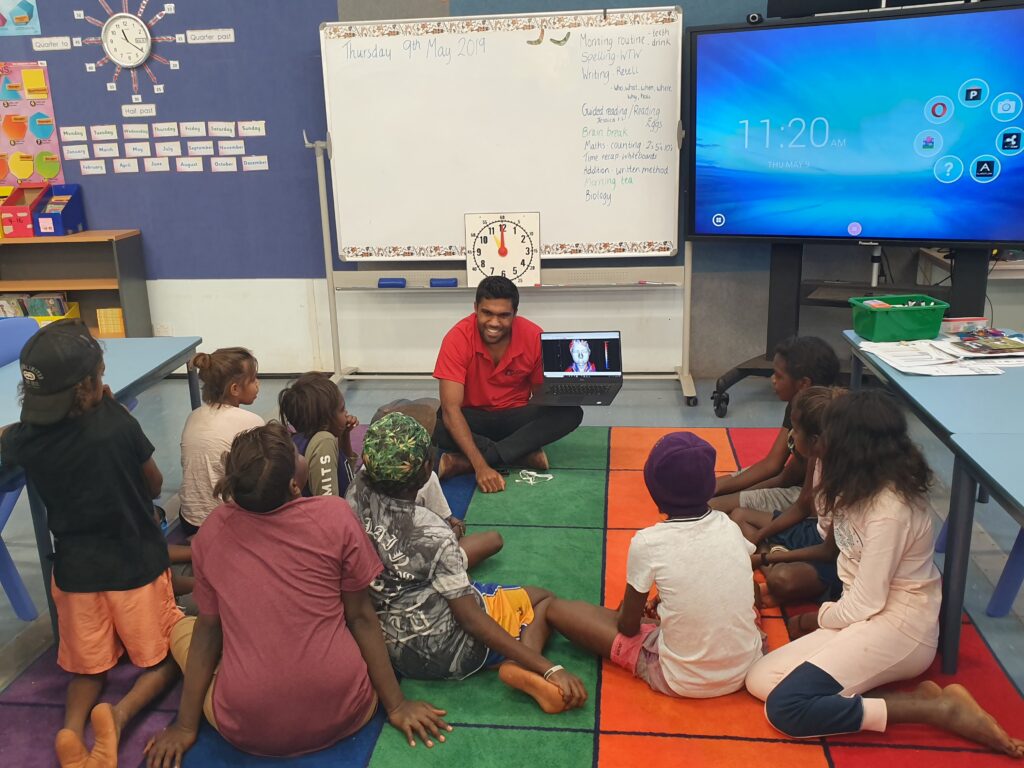

Beginning in a remote area in the Australian desert, Gareth and his team worked with a then medical student, Yarlalu Thomas, and his family, crudely using paper, pencils and a microphone to do the translations. Following this, other Indigenous youth learnt about the project and a network of participants grew organically representing multiple languages and communities.

For Gareth the aim was always to begin in rare disease and expand outwards to encompass all health conditions. “We launched it in rare disease as there’s such a huge need in this area that we wanted to help address and try to close that gap. We also knew that, because rare disease is such a great innovation place, anything we do in the rare disease space could help with all human health.”

The project proved invaluable during the Covid-19 pandemic, when there was no public health messaging available in Indigenous languages. The youth very quickly mobilised to produce one-page documents, in as little as 48 hours, in their native languages to disseminate throughout their communities. “It’s probably the fastest public health response I’ve seen,” remarks Gareth.

Upscaling and giving back to the communities

The project, which gained the name ‘Lyfe Languages’, now provides a free web-based app, and, for Gareth, it is important the app remains free. He set up a not for profit with gift recipient status to ensure the way they work returns maximum benefit back to the community.

There are more than 200 Aboriginal languages, some that overlap with other languages and some that don’t, and so the modules offered by ‘Lyfe Languages’ can be separated out into their visual and audio components and uploaded independently meaning animations, for example, can be overlayed with multiple languages. This helps when scaling the project.

The team have worked with universities and hospitals locally in Australia and in Singapore, to create virtual reality tools for medical education. Originally tagged in English, Aboriginal languages are now available. Another artificial intelligence (AI) tool, called Utopia, creates personalised natural history studies for people with rare disease to enable their care coordination and planning. The aim is to start to weave the ‘Lyfe Languages’ system into this model.

A circular benefit model

The young people who work on the translations are called ‘Lyfe Language Champions’, and have access to a mentoring programme, where they are paired up with mentors who work in a domain they are interested in. For example, the founding Lyfe Champion, Yarlalu Thomas, was paired up with the chief medical officer of Microsoft, Australia and New Zealand. “Whatever they want support in we’ll try and find mentors for them, and that obviously then leads into capacity building and employment opportunities.”

Language matters

The personal motivation for Gareth in setting up ‘Lyfe Languages’, was seeing the vast inequity in healthcare, with communities having little or no access to services tailored for them, instead relying on family members to play the role of translators. A young person shared with Gareth the story of his grandmother attending a medial appointment. To bring the appointment to a close, the doctor said, ‘you’re finished’. In the lady’s culture finished means you’re dying, and so she returned home, stopped taking her medication and became very ill. Language matters.

“How can you build trust, have a rapport, have any decent sort of interaction at a personal level or a medical level, if you don’t have an ability to talk to each other in language,” questions Gareth.

The team have worked with a remote community in Australia on a project for Huntington’s disease. The community are surrounded by waterways and so the translators use the analogy of rivers being blocked to explain the toxic accumulation common in Huntington’s disease. As Gareth explains, “It’s not just about the words, it’s about using the community narratives. For genes and genetic information, we use the analogy of songlines which is how knowledge is transmitted by Aboriginal people, between and within generations. It’s about doing things in a way that resonates with the communities because that’s how memory works. Memory anchors the things that are familiar and so by using familiar concepts and constructs you’ve got much more chance of the message being remembered.”

For healthcare professionals, having a tool or means by which they can connect with and explain medical information to their patients helps to build trust and provide a more inclusive, equitable service. “Having a narrative to explain a concept, even without direct translation of words, in concepts that resonate with the community makes a huge difference. Or even just having a few words to use is enough to say, ‘I care’, and I think that improves engagement.”

Addressing inequities in healthcare and clinical trials

Addressing issues of diversity and inequity in healthcare is pivotal to the drive behind the project. As Gareth notes, racism is still a significant issue for the Aboriginal communities, particularly in rare disease, and can affect who receives medical referrals. Gareth sees a real opportunity to make a difference, innovate and effect change, especially because the need is so high. “If you develop a process that works in a low resource, remote area, where English is a second, third or fourth language, that’s going to work for everybody.”

“There’s a real opportunity to address massive inequity and help everyone, and I think there’s a real beauty in that.” Gareth

Gareth is keen to develop ‘Lyfe Language’ modules for clinical trials, an area with significant inequity. “In the rare disease space only 5% of rare diseases have treatment, and so the only hope for many people for drug treatment is access to a clinical trial. We know that First Nations people have disproportionately low access to clinical trials, and a significant component of that is language.” He expands to say it’s important, particularly in the rare disease space, to maximise the number of people who access a trial because it’s a small-N problem, referring to the challenges when working with small sample sizes.

For this reason, Gareth is actively seeking partnerships to upscale and further develop ‘Lyfe Languages’ to address this inequity and increase access to clinical trials for Indigenous people. “There’s no area of greater need for equitable access to trials than rare disease, because you’ve really got to maximise everything you do to get your numbers, to make your trial feasible and sustainable. I think of all the areas in medicine in terms of trying to overcome inequity, clinical trials access is fundamentally the most important.”

To learn more about the inequities in clinical trials, please access the paper ‘Increasing diversity, equity and accessibility in rare disease trials’here

Or for more information about ‘Lyfe Languages’ visit the websitehere

Using the analogy of songlines for genetic information

If you are in interested in learning more about how you or your company can support the future growth of ‘Lyfe Languages’ please connect with Gareth below.

Connect with Gareth

References

[1,2] https://en.iyil2019.org/about/index.html

in the round connects you to your global RARE community. To access more in the round articles click below.