When policy fails people: Reimagining medicines access for rare conditions

Written by Henry Burkitt, managing director, Oxygen Strategy

Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

The UK is approaching a critical juncture in how we assess, reward and enable access to new medicines. On one side of the trench stands industry, arguing that punitive rebate rates under the Voluntary Scheme for Branded Medicines Pricing, Access and Growth (VPAG) are stifling innovation and deterring investment. On the other, government and health system leaders maintain that controlling medicines spend is vital for NHS sustainability. Caught in the crossfire are people living with treatable conditions and their carers whose voices are often lost amidst the clash of lobbying narratives

Let’s be honest: the current structure of VPAG is not fit for purpose. It is the latest iteration of a cost-containment model that dates back decades, originally designed as a short-term fiscal tool during periods of economic constraint. The introduction of the rebate in the 2014 PPRS (the precursor to VPAG) reflected post-financial crisis government priorities: ensuring predictability and control over NHS branded medicines expenditure in the face of austerity and growing pressure from high-cost therapies.

Yet, in 2025 we’re still applying that same blunt instrument to a very different set of challenges. VPAG is a relic. It sets a single branded medicines spending cap and applies flat rebate rates—up to 35%—with no distinction between lower-value therapies and truly transformational innovations. It does nothing to prioritise uptake, accelerate adoption or reward system value. Worse, because the scheme pools all branded sales under one national cap, companies with modest revenues are effectively subsidising those with high-growth portfolios. The collective pays for the outperformance of a few. This is not a system designed to maximise health outcomes, improve equity or encourage the kinds of therapeutic breakthroughs rare disease communities so desperately need. It is a system built for fiscal accounting, not health impact.

At the same time, industry appears stuck like a broken record with its messaging and strategic posture. Too often, the narrative surrounding high-profile medicine rejections is used as a proxy for wider system failure. But not all rejections are created equal.

Some drugs are rightly declined due to legitimate uncertainty over their clinical effectiveness, safety or long-term benefit. Others are rejected due to deeper structural limitations within the system and inadequacies that do not necessarily reflect societal values or patient need.

There are other systematic oddities too. For example, when a new medicine offers only a modest benefit over a high-cost comparator, it can still be rewarded within the cost-effectiveness threshold. But paradoxically, when a genuinely step-change innovation emerges and is compared to a much cheaper standard of care, its apparent cost-effectiveness is penalised. This asymmetry discourages true innovation which rare disease communities rely upon.

In my experience of supporting companies through dozens of NICE evaluations, I can see that these nuances matter. We cannot credibly argue that every new medicine should be made available. But neither should we accept a system that fails to differentiate clearly and rationally between what society values, what the NHS needs and what innovation is worth paying for.

One argument that has gone largely unchallenged is that the UK has long benefitted from a good deal: relatively high R&D activity, extremely low per capita medicines spend and reasonably strong access by international standards. For a while, this model worked. But the trend is now clear and deeply worrying. The UK is slipping down the list of priority launch markets in global boardrooms. There is no question that rebate rates and squeezed margins have tipped the UK into the ‘not worth it’ column for more and more global launches. This is not sustainable. There needs to be a rethink about what we pay for medicines in this country, but it needs to be done in a way that is intellectually coherent, differentiated and rooted in evidence.

We must stop linking overall medicines spend to health outcomes in broad brush terms. Instead, we should ask: where do we need innovation? Where does it deliver genuine value? And how do we ensure that companies offering those innovations can make a fair return?

Imagine if our regulatory, HTA, access and NHS adoption systems were aligned around a shared ambition: to be the best country in the industrialised world at taking up impactful new treatments? Right now, NICE’s five-year post-launch uptake curve sits at just 0.75 of the median. But with real-world evidence, coordinated data flows, system readiness and pricing aligned to outcomes, we could become a leader. We have the data infrastructure. We have the clinical talent. We have a national health service that could deliver joined-up impact. What we lack is the leadership, ambition and political will to do it.

There are signs of hope. Two areas of active policy development could lay the foundation for more meaningful reform. First, NICE’s proposal to lower its discount rate from 3.5% to 1.5% would better reflect the value of long-term health benefits, helping treatments that accrue benefits over many years (a common feature in rare disease therapies). Second, NICE’s societal preferences research could transform how we evaluate severity and unmet need, providing a more morally credible basis for valuing therapies for ultra-rare and severely disabling conditions.

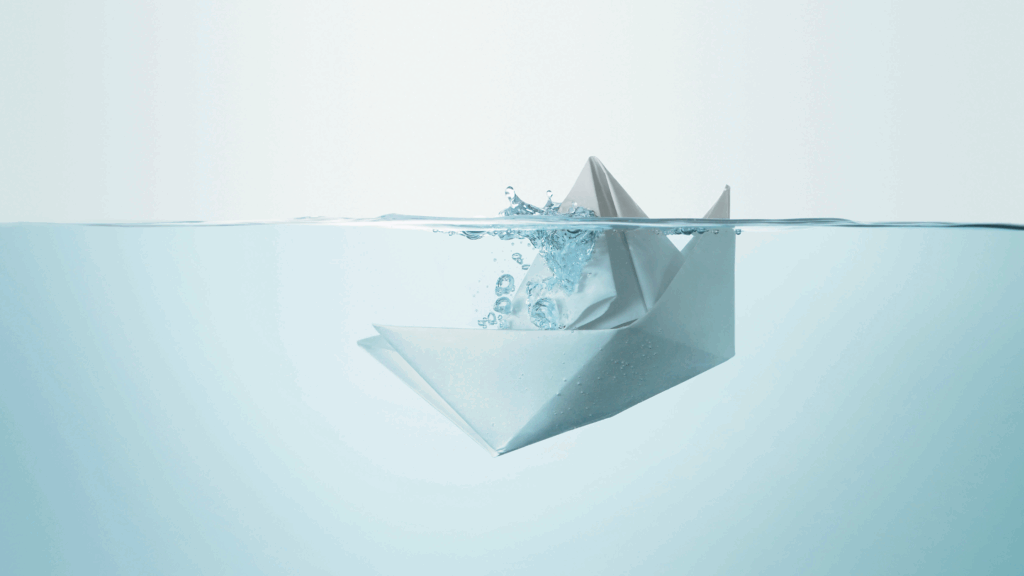

But even these modest reforms are at risk of being sidelined. Because the policy bandwidth is consumed by VPAG rebate arguments, we are failing to build the frameworks that could actually transform HTA in this country. We are rearranging the deckchairs on the Titanic.

It doesn’t have to be this way. What we need is a complete rethink of how we design a system that delivers for all stakeholders:

· For patients, it must mean earlier, faster access to life-changing therapies, particularly where no alternatives exist.

· For the NHS, it must mean value-for-money assessments that reward outcomes, not just unit costs.

· For society, it must reflect a fair allocation of resources and support for long-term public health priorities.

· And for industry, it must offer predictable and meaningful rewards for genuinely innovative products that solve real problems.

The rare disease community knows all too well what happens when systems fail to evolve. Too many families still face diagnostic odysseys, patchy specialist care and empty medicine cabinets. They deserve better than a policy argument about rebates and thresholds that feels disconnected from their lived reality.

This is a moment for fresh thinking. It’s time to design an access and pricing framework that doesn’t just serve government and industry, but the people whose lives and futures depend on it.

Because for people living with a rare condition, this isn’t just policy. It’s personal.

Connect with Henry

in the know brings you the latest conversations from the RARE think tank. To access more in the know articles click below.