Recognising Rett: professional and personal perspectives on diagnostic challenges for Rett syndrome

FUNDED BY ACADIA PHARMACEUTICALS GMBH

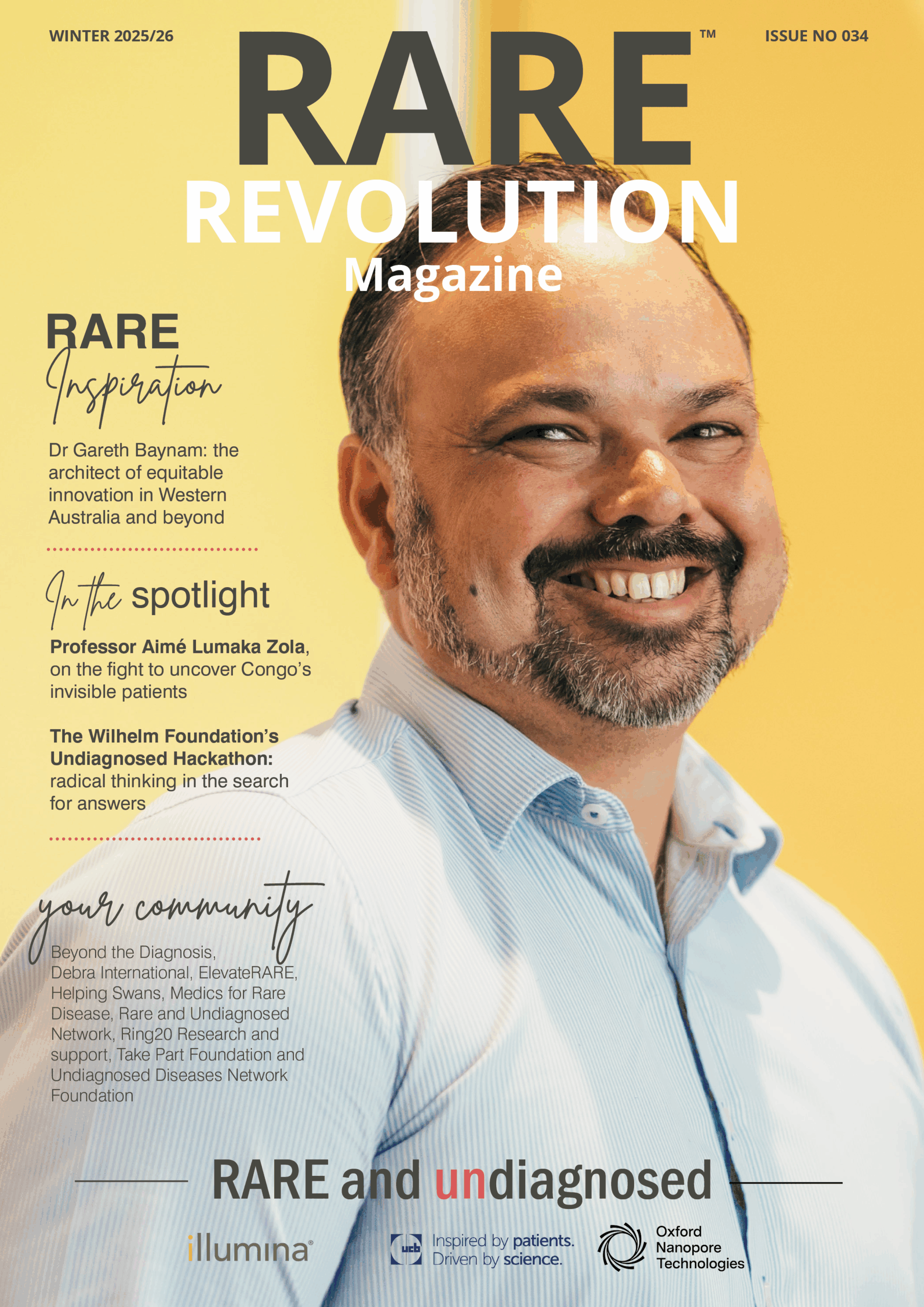

Rett syndrome is a rare, complex neurodevelopmental disorder that poses significant diagnostic challenges. Professor Siddharth Banka, a leading clinical geneticist and director of the Manchester Rare Condition Centre in the UK, shares his insights. He discusses the importance of accurate genetic diagnosis, the barriers families face, and how emerging technologies and improved clinical pathways can better the diagnostic process for individuals like Hannah Manby, whose parents Chris and Becky, are still learning to come to terms with her recent diagnosis

Written by Nicola Miller, RARE Revolution

Professor Siddharth Banka, clinical geneticist, professor of genomic medicine and rare disease, Manchester University, director of Manchester Rare Condition Centre and lead consultant, Rett syndrome specialist clinic, Manchester

Chris and Becky Manby, rare parents and advocates

Rett syndrome is a rare, severe neurodevelopmental disorder that almost exclusively affects females* and is caused by mutations in the MECP2 gene on the X chromosome. Typically, girls with Rett syndrome develop normally for the first 6–18 months before experiencing a loss of acquired skills such as speech and mobility, along with distinctive symptoms like stereotypic hand movements (repetitive wringing), developmental delays and autonomic dysfunction (including difficulties with breathing and temperature regulation). The condition can also involve feeding difficulties, scoliosis (curvature of the spine), and other health complications like frequent urinary tract infections, constipation and gallstones. Epilepsy is a common associated comorbidity. Early signs typically present aged 6-18 months, with signs of regression between 1-4 years of age. The school years and early adolescence typically see developmental regression stabilise, with greater need for ongoing surveillance of breathing, feeding and spinal issues.1 In adulthood, individuals with Rett syndrome are often non-verbal, lose purposeful use of their hands and many lose mobility to some extent and become wheelchair users, requiring lifelong, multidisciplinary support to manage their complex needs.

*Rett syndrome and boys – Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in the MECP2 gene located on the X chromosome. Because boys have only one X chromosome, mutations in this gene typically result in more severe symptoms and are often fatal—many times before birth or early infancy within days of birth, which, is why classic Rett syndrome is rarely seen in boys. In rare cases, boys with atypical forms of Rett syndrome may survive longer, especially if they have an extra X chromosome (as in Klinefelter syndrome) or mosaicism, but their symptoms are still usually more severe than those seen in girls. As a result, the vast majority of individuals diagnosed with Rett syndrome are female, and cases in boys remain extremely uncommon, but important to note—not impossible.

While classic Rett syndrome follows this well-defined pattern, advances in genetic testing have revealed a broader spectrum of MECP2-related disorders, including atypical forms with milder or more variable symptoms.

Some related conditions, caused by mutations in other genes, may overlap clinically but are now recognised as distinct, which Professor Siddharth Banka, clinical geneticist, is keen to emphasise that in his opinion, “It’s important to recognise that Rett syndrome is fundamentally a genetic diagnosis—while clinical features guide suspicion, relying solely on clinical definitions can be misleading, and conditions with different molecular causes shouldn’t be clustered together. This distinction matters because accurate diagnosis ensures patients receive the most appropriate care and that advances in treatment and research are correctly targeted.”

Accurate diagnosis of Rett syndrome relies on genetic testing, which is very helpful for guiding management and understanding prognosis—there is currently no cure, and treatment remains supportive. However, the path to a diagnosis starts much earlier as Siddharth explains, “Early red flags for Rett syndrome often present as a child (typically a girl), who was developing normally, and then their development stalls.” He adds, another key sign is the “loss of skills they previously had, like self-feeding, crawling, fine and gross motor skills and even speech. They might have already learned some words, but they stop using those words.” Parents are usually the first to notice these subtle changes and would typically raise them with their health visitor in the first instance and then their GP.

But this presents the first challenge in a timely diagnosis, as husband and wife, Chris and Becky Manby, explain. In the months leading up to their daughter, Hannah’s, diagnosis, Chris and Becky noticed she “developed quite normally until she was around 10-11 months,” but then Becky noticed she wasn’t doing things her older sister had done at the same age—like crawling. Despite raising concerns, Becky explains, “the health visitor wanted to wait till she was 18 months before doing anything.” This left the couple uneasy: “We weren’t happy to do that at all.” Becky recalls, “after the age of 12 months, she started losing skills that she’d already had—she stopped feeding herself, she stopped holding toys, and she held her hands in a distinct way.” Frustrated by a lack of urgency and delays in the system, they decided to fund a consultation with a private paediatrician. It was this crucial step that ultimately set them on the path to a formal diagnosis, and Becky is confident had they not done this they would still be following the ‘watch and wait’ protocol favoured by her heath visitor.

This picture for families like the Manbys is further clouded by the complexity and length of the diagnostic pathway. As Siddharth explains, “the challenge is how quickly the testing is initiated, which relies on how quickly the patient presents to a health visitor or relevant clinician, then the speed of referral by the GP or paediatrician to the right clinic.” The process often involves multiple steps: initial concerns raised by parents, reassurance or referral by health visitors or GPs, typically repetition of raised concerns after a period of no improvement or continued regression, preliminary genetic tests such as microarray analysis, and only then, if necessary, further referral to specialists for genetic testing with targeted MECP2 testing, gene panel testing or whole exome or genome sequencing (WGS). Each stage can introduce weeks or even months of delay, compounded by paperwork, consent procedures and the time required for testing which can be up to several months for WGS. As Siddharth highlights “the challenge is less technical, and rather more around the clinical pathways and around how quickly parents and the health visitors realise that there might be some difference and how quickly the child is started down that pathway.” Then it is down to how fast the child can move through the referrals process to ultimate testing and communication of results.

With thousands of rare diseases, it is difficult for frontline healthcare providers to recognise every possible condition, something which Chris, Becky and Siddharth all agreed on. As Siddharth notes, “there’s always more training that could be done, but we must acknowledge that with over 8,000 rare disease we cannot expect health visitors to be informed on the nuance of each. Their training is in supporting infants and parents, not in diagnosing rare and complex diseases.”

But of course, as new parents, this lack of knowledge or medical curiosity remains frustrating. Chris and Becky both expressed deep frustration that “the health visitor didn’t appear to take their observations seriously,” with Becky recalling, “I knew my child was different and things were not right, and I felt they were not listening to me.” Chris emphasised the importance of listening to parents, urging that “health professionals should realise the power of intuition of a mother”, which as he adds, “is incredibly strong and should not be ignored.”

While increasing awareness and education for these primary providers is important, Siddharth feels that to improve the diagnostic process, the focus should be on streamlining referral pathways, ensuring timely access to specialised expertise and advanced testing. This should include the provision of clear guidelines for when to escalate concerns, which could help reduce delays and ensure that children with Rett syndrome are identified and supported as early as possible.

A delayed diagnosis can have profound emotional and practical impacts on families. As Siddharth explains, “there is currently a whole, complicated, long and drawn out process,” and the uncertainty can be distressing for parents who sense something is wrong but lack answers. While sometimes “having that gap between presentation and confirmed diagnosis might even be helpful to some families—where it helps them to process the information that the child, who they thought was developing completely normally, may have a genetic condition for which there is no treatment available—for many, the wait is a source of anxiety and frustration.”

It’s important to also consider the delivery and communication of a diagnosis like Rett. Siddharth emphasises, “we would never deliver such a serious diagnosis over the phone for example. We would always want the family to be there in the clinic for us to be able to communicate it sensitively. That’s important. It also allows us to ensure that the information conveyed is accurate and that it is understood correctly.” A timely and compassionate approach, guided by experts in the disease, ensures families are supported, informed and able to process the life-changing news in the best possible environment.

By contrast, when a diagnosis is not delivered by experts, it can leave families with more questions than answers, which as Chris and Becky explain, can leave them in an anxiety inducing limbo.

Much like the wait in receiving a diagnosis, the delivery of Hannah’s diagnosis was a process equally fraught with uncertainty. Chris felt the generalist paediatrician, who delivered their confirmed diagnosis, knew nothing of Rett. “He seemed to know as much as we did from our Google search,” Chris explains. “He wasn’t able to answer any of our questions about Hannah and Rett syndrome in a meaningful way.” This lack of expertise left them having to drive everything: “we had to ask them to do basic things, like make a referral to a specialist, and guide who we needed to see.” Now, months post-diagnosis, they remain on the waiting list. As yet they have had no further post diagnosis follow up or consultation with a specialist who truly understands the disease. The absence of clear guidance has forced Chris into the role of expert: “the only way I cope with it, is to research therapies and look at other children with the same disease to help understand the prognosis.” The ongoing limbo and responsibility to find answers themselves have added to the emotional toll, with Chris plagued with worries about Hannah’s future. The agony of having to sit and wait it out, while they languish on an NHS waiting list, has driven the couple to seek out privately funded physical and speech and language therapy. But they admit that without expert guidance they are unclear on what early interventions would be most beneficial. In the meantime, they rely on the support and guidance of other families and online support group forums.

Emerging technologies and initiatives, particularly newborn genome screening and advanced genetic sequencing, have significant potential to improve the diagnosis of Rett syndrome. As Siddharth explains, “from a diagnostic point of view, newborn genome screening programmes will obviously help to get to diagnosis much quicker—soon after birth.” This could enable earlier identification of Rett syndrome, even before symptoms appear. However, Siddharth also points out important limitations: “Whether that’s the right thing or not for Rett syndrome is a point of debate, especially when there is no treatment available for most. It’s also a matter of resources, both financial, and human resource capital—to find one child with Rett you must sequence around 30,000 babies.” So, while technologies like genome sequencing and data-driven diagnostics hold great promise for earlier and more accurate diagnosis, their widespread adoption will require careful consideration of resources, infrastructure and ethical considerations.

For now, achieving an accurate and timely diagnoses for Rett syndrome remains a challenge—much of the emphasise and responsibility laying at the feet of parents to push for investigations and drive the care and support they need in those early months and years. But it is also clear that much can be done to improve this experience for families, if adequate escalation guidelines were widely adopted and referral processes streamlined. This would go a long way toward moving a child from that first flicker of parental intuition, displayed by Chris and Becky, to being sat in front of a knowledgeable professional like Siddharth who can help be an important partner in a family’s journey and share the load.

About Professor Siddharth Banka

Professor Siddharth Banka is a clinical geneticist based in Manchester and a professor of genomic medicine and rare diseases at the University of Manchester. He leads the Rett syndrome specialist clinic within a large clinical genetics department and serves as the clinical director of the Manchester Rare Condition Centre, which he helped establish. Additionally, Siddharth is a co-lead for the NHS England Rare and Inherited Disease Network of Excellence. His work centres on the discovery of new genetic disorders, understanding disease mechanisms and clinical features, conducting clinical trials for rare diseases and improving diagnostic pathways to enable earlier and more accurate diagnoses for patients with rare genetic conditions.

Reference:

[1] https://www.reverserett.org.uk/infomation-about-rett/what-are-the-symptoms-of-rett-syndrome/

Articles within this digital spotlight are for information only and do not form the basis of medical advice. Individuals should always seek the guidance of their medical team before making changes to their treatment.

This digital spotlight has been made possible with financial support from Acadia Pharmaceuticals GmbH. They have had no editorial control over the copy, and all opinions are those of the contributor.

RARE Revolution Publishing® retains all copyright.