My unexpected journey: life with a rare liver tumour

Madison Moore was oblivious to any health issue until the sudden onset of debilitating pain that saw her admitted by ambulance to her local hospital. Investigations revealed a 17cm tumour occupying 70% of her liver. This finding indicated a diagnosis of hepatic adenoma and latterly a further rare diagnosis of May-Thurner syndrome

Written by Madison Moore

My journey began very suddenly this past May when I was home for spring break visiting family. At first, I thought it was something simple—maybe a pulled muscle from overdoing it at the gym? But the pain worsened, sharper and deeper, until the paramedics were called and I was loaded into an ambulance. My local hospital performed one scan before labelling me a liability and shipping me to a level one trauma care centre in Chicago. There, blood work showed severely abnormal liver enzymes (typically about 20, mine exceeded 1,500) and imaging revealed something I never expected: a giant, haemorrhaged liver tumour.

The words “hepatic adenoma” were new to me. I remember staring at the doctor as he explained that it was a benign mass of the liver, most often linked to hormone imbalances. I had so many questions. Could this become cancer? Would it rupture again? What would this mean for my future? I’m only 23 years old, too young to even think about my liver failing.

The hardest part in those early weeks was the unknown. Every scan, every lab test felt like a waiting game. I learned quickly that hepatic adenomas are exceedingly rare, about one case per 1,000,000 people overall. Mine had already haemorrhaged, causing internal bleeding and explaining the searing pain that sent me to the hospital. Suddenly I was living with the reality that my liver, something I had never once thought about, could change my entire life.

I was referred to a care team who explained the options. Hepatic adenomas are typically about 5cm in size and can be removed via liver resection surgery. Mine, however, was 17cm and occupying 70% of my liver. It was compressing my stomach, hepatic artery, portal vein, and the inferior vena cava of my heart. Because it was massive, filled with blood, and touching major blood vessels, removal or transplant were not considered safe possibilities. I spent a month in the intensive care unit being monitored closely as we mapped out a plan. I had an embolisation surgery to kill the blood flow that was feeding the tumour and ensure that it could not grow any larger. I also had a biliary drain placed and underwent weekly tPA (tissue plasminogen activator) infusions to break up the blood clots within the tumour. My family became my anchor throughout the entire process, never leaving my side and constantly reminding me how strong I was.

It was expressed to me by every hepatobiliary surgeon I met that a 17cm tumour haemorrhaging in the body is typically a death sentence. The survival rate for this occurrence, they advised, was0.007%. I was incredibly lucky that my adenoma essentially imploded, bleeding into my liver, rather than exploded, which I would not have survived. My doctors informed me that in all their years of practicing, they had never seen anything like this.

Throughout the ten CT scans I had over the course of two months, another rare condition, May-Thurner syndrome, was identified. It occurs when the iliac artery, which sends blood to your legs, presses on the iliac vein, which carries blood to your heart. Additionally, my cardiologist determined a dysautonomia diagnosis, which is a condition where the autonomic nervous system doesn’t work properly, affecting involuntary functions like heart rate, blood pressure, and digestion. I had been fainting for three years prior, so I definitely saw this one coming, but my tumor only exacerbated the symptoms.

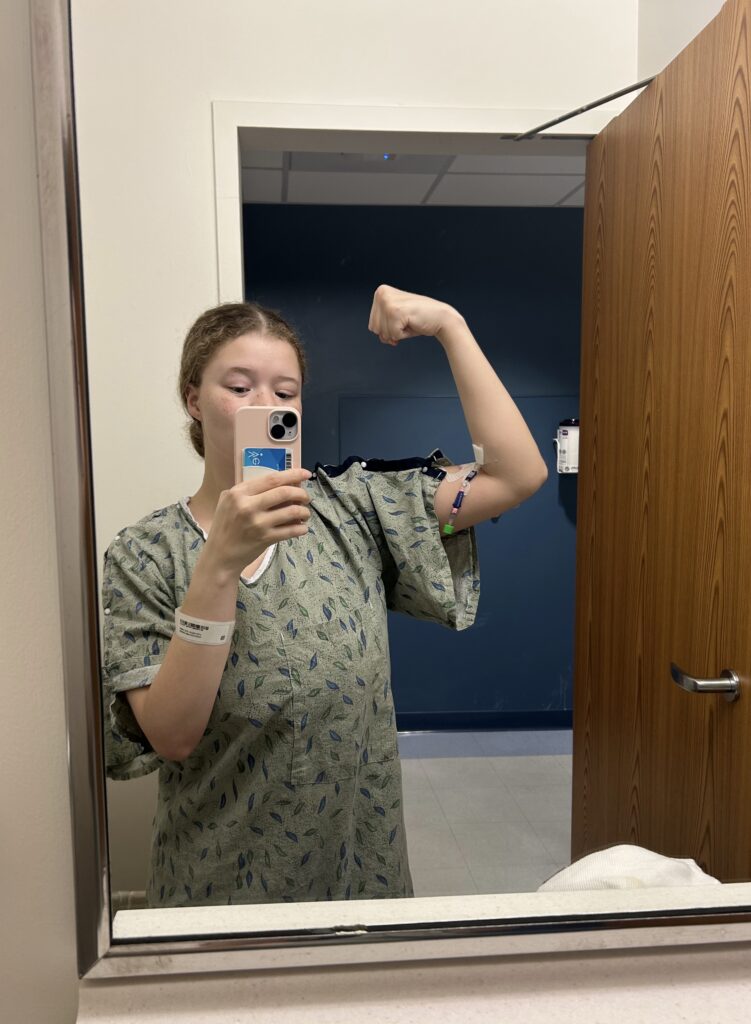

Living with a hepatic adenoma isn’t obvious to anyone who sees me. On the outside, I look “fine.” But inside, I’m constantly aware of my liver tumour—the aches after too much activity, the fatigue that sneaks up without warning, the fear of relapsing symptoms. It’s an invisible disability and with that comes the isolation of people not truly understanding what you carry.

When I use certain accommodations, people just assume I’m being lazy and taking advantage. For instance, sometimes I need wheelchair assistance at the grocery store and workers take a skeptical, judgmental glance before begrudgingly offering one. They think that because I’m standing, I can walk just fine. But trust me, an 8lb tumour and a circulatory disorder combined with chronic fainting creates a spectacle worth avoiding if at all possible.

Over time, I’ve learned to focus on what I can control: following up with specialists, listening to my body, and shifting my mindset towards gratitude for the fact that I’m still living. I’ve joined patient groups online and found comfort in connecting with others who know the language and hardships of liver disease. There is strength in not feeling alone.

Today, I am grateful. Grateful for doctors who listen. Grateful to be returning to graduate school after a semester spent in the hospital. Grateful for the support system that reminds me daily that I am more than this disease.